a map. a story. a treaty.

reflections on the story of Waitangi. a story that didn’t begin with the Treaty, but a story that requires ongoing partnership, reciprocity and autonomy

In early February within our Service Innovation Team at Te Tari Taiwhenua, we ran an activity to reflect on Waitangi Day. This was led by a small group of GovTech interns, who alongside our hosts at Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga and several Service Innovation Lab staff all shared their story of what Waitangi Day means to them.

We told these stories at various locations around the Department of Internal Affairs. We started on Level 10 and then 8 in the Pipitea Street building, moved to Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga, and then finished at Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa, inside the He Tohu exhibit.

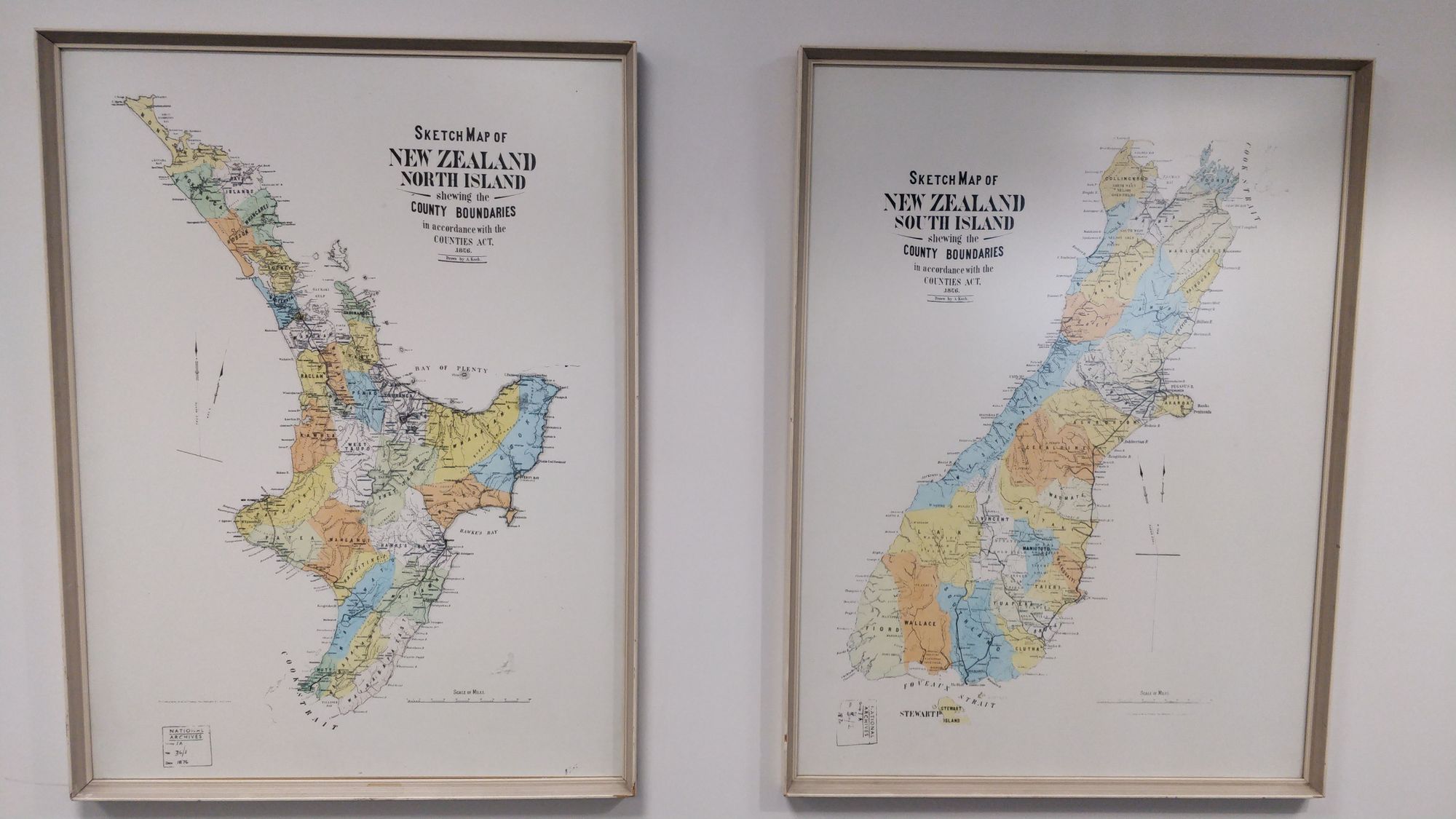

This was my story - told on the 8th floor of the Pipitea Street building, while looking at this map.

"I grew up in South East Asia. My parents had a subscription to National Geographic. I always loved looking at the maps that were available as inserts. I loved poring over these strange exotic faraway places, with names like Christchurch or Matuara, or Whanganui, from my vantage point of the little fishing town of Pattani, South Thailand.

I loved those maps because I was never at the centre of them. I knew where I was on those maps, but the layout and design of them meant I could see other places and consider them. Those maps told me stories about strange places - and I could make up stories about how I was related to those places, or maybe, one day, could be. They were a lens by which I made my sense of, and connected with those places.

We each carry a story in us of the Treaty, of Waitangi Day, and of what it means to us living here. We all carry a lens by which we define and imagine those stories, and those stories in turn define us as we go about our work and our daily living.

This pause today, is to reflect on your own story through the lens of a map. That is by considering the land and time those maps are formed in, to consider how as a result, those maps invisibly shape our perception of our place in Aotearoa/New Zealand now.

Our story starts a few years ago.

According to the Te Ara website in approximately 1300, Māori arrived in Aotearoa and 450 odd years later, the Europeans show up.

Between 1769 and 1777, James Cook becomes the first European to map and document the outline of these islands.

In 1835, the Declaration of Independence was signed by Māori and recognised by the international community - enabling trade and diplomacy between Te Ika a Maui and the globe.

In 1840 the Treaty is signed, and these islands become a British colony.

Also in 1840 the “Colonial Secretary’s Office” is established - with the Colonial Secretary, the first one being Willoughby Shortland, serving the Governor. The first governor was of course…. William Hobson. When in 1907, NZ became a Dominion, this office would be split up into a number of functions, including the Department of Internal Affairs.

When I first saw this map, I was struck by the date on it - 1876 - and I realised that this map reflects that in 1854, provinces were established to take over many government or Crown functions. So maps like this were produced to help manage and organise the functions of the Crown.

So this map was only 36 years after the treaty was signed.

What story of these islands does it tell?

Looking at this map - how familiar does it feel to you?

What is your connection with the places and names on this map?

For me I recognise places I’ve been on holiday - or where my family live. I would use it in everyday language - “Have you been to Buller-Westland? When was the last time you visited Marlborough?”

How much of your story - your understanding of New Zealand/Aotearoa, and your place in it - is embodied and apparent this map?

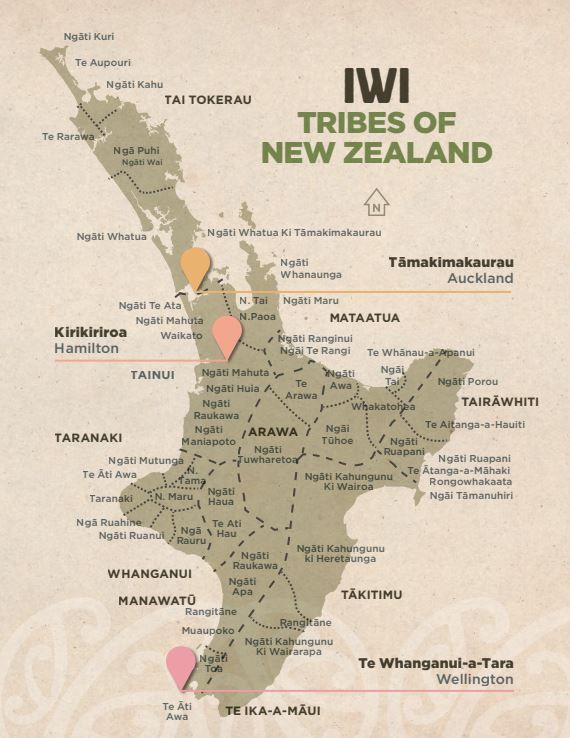

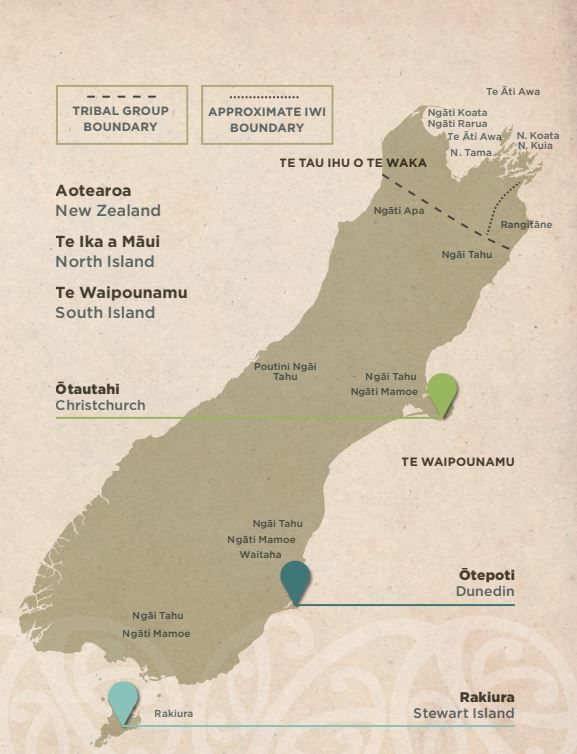

Now I want you to look at this handout - a resource created by NZTE.

When you look at this map - What do you notice?

How familiar does it feel?

Do you know these names?

Do you know these lines?

How is it different from the map here on wall?

For both maps - what story is represented on them.

What is not represented?

Which map represents your story?

Is your understanding of yourself and your family visible in this map?

Or this one?

One map here on the wall captures the early output of the organisation that we work for each day.

We are representatives of the Crown, a Crown that about 180 years ago drew invisible lines to define a land, a land where people have been living for over 4000 years.

As a child, I had a New Zealand passport, but I learned about New Zealand through maps and newspaper stories, and seeing the odd bit of fuzzy TV about the All Blacks. I grew up flying backwards and forwards between SE Asia and New Zealand, from when I was 3 months old to when my parents moved back permanently to Christchurch in 1991.

It took me probably about 5 years to be able to say for myself that Aotearoa was the place I chose to call home. My place to stand. My turangawaewae.

I still remember that moment - I was flying back from a trip to visit friends in the USA, and I was looking out the window of a 747, watching those marshy fields appear below the wing, on the landing into Tāmaki Makaurau. And after dozens of that same landing, over the course of a lifetime of flying in and out of this land, that was the first time I felt it in my bones, and could say it whole heartedly that I was home.

Now twenty five odd years later, after a decade in education, where I’ve learned a modicum of te reo and some tikanga around working with what the Crown labels as “priority learners” - it’s a privilege to be standing here to learn more of this story, the one embodied in this iwi map.

Because I’m learning more about that perspective, not just in our te reo sessions, but also each time we look at an issue or a reality that is brought to the Lab. I’m increasingly aware of how each of these discussions, these scoping conversations, these “pain points” that the Crown needs to identify and work on as we build better services, need to be seen as through the lens of the Treaty, and the spirit of partnership.

And so this map, as buried as it is in this building, is a reminder to me, to consider how we view this land, and how we view the people we serve.

More importantly, how we’ve not viewed people.

How we’ve not viewed the land.

How we’ve made parts of the stories of this land invisible and unrecognizable.

I wonder how we as individuals, as public servants, and as a society are able to honour the intent and spirit of tino rangatiratanga and the principle of partnership; if we fail to recognise the simple and yet powerful way that maps shape our invisible biases and understandings of the land we walk on.

For me, neither of these maps are greater than the other - they are of course a matter of perspective, and I think the ongoing challenge is for us to visibly honour each other’s perspective, to reflect on the stories that both maps represent.

To act accordingly as individuals.

To design and build services accordingly.

To carve new shared stories that honour both.

If you only know and identify with one of these maps, and with one story, you miss the shared story.

A story that didn’t begin with the Treaty, but a story that requires ongoing partnership, reciprocity and autonomy."